The Kirstead Taylors Part 6

The Kirstead Taylors

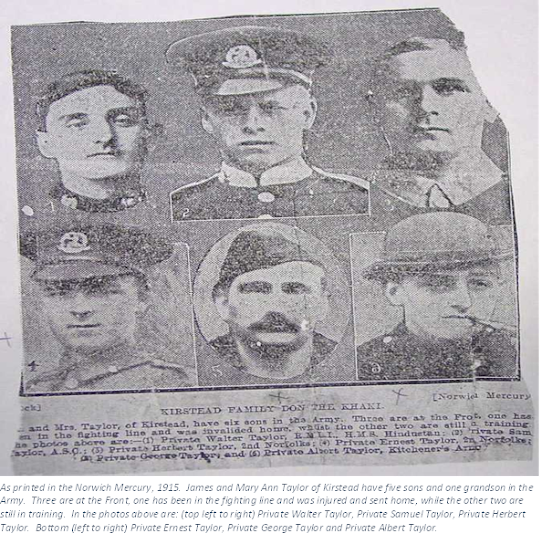

A Newspaper cutting 'Kirstead Family Don Khaki', a captioned photograph montage of the six Taylor brothers in uniform, the sons of Mrs. Mary Ann Taylor and the late James Taylor of 42 Kirstead Ling, Brooke, Norwich. Three of the brothers were killed in June - July 1916, and are remembered on the Kirstead Green War Memorial.

Margaret Florence Taylor (1889-1927). Margaret was the 10th child born to James Taylor and Mary Ann Powles. Born in Kirstead, Norfolk, England on October 31, 1889. She emigrated to Quebec, Canada on August 13, 1911 and settled in Port Williams, Nova Scotia, Canada. She met and married George Henry Graves on March 4, 1912. Their children were William Andrew (1912-1979), Daisy Olive (1914-2014), Florence (1920- Bef. 2014), Albert ( -Bef. 2014) and Dorothy ( unk).

Rosie “Rosa” Jane Taylor (1892-1944). Rosa was the 11th child born to James Taylor and Mary Ann Powles. Born in Kirstead, Norfolk, England on January 15, 1892. At the age of 9 she was living with her sister Mary Ann and her husband Charles Alfred Buck. At the age of 19 she was working as a domestic servant in the household of Dr. William Spowart and his family. Rosa Jane married Edward Green Riseborough (1888-1980) in January 1914 in Loddon, Norfolk, England. Together, they raised two children. They were Albert Edward (1916-2011) and Herbert J. (1920-2005). No doubt that her children were named after their uncles, but it is a strange coincidence that her firstborn son, Albert Edward was named after both Albert Taylor who died in WWI on June 4th and Ernest Edward who died on the same battlefield as his brother on June 21, 1916. Their uncles deaths occurring within days after Albert Edward’s birth.

Ernest Edward Taylor (1893-1916). (pictured in the montage from the Norwich Mercury in the lower left) Ernest Edward was the 12th child born to James Taylor and Mary Ann Powles. Born in Kirstead, Norfolk, England in August 1893. In 1911, Ernest was listed in the census as 18 years of age and working alongside his older brothers George and Albert as a farm labourer. Most likely for local farmers Mr. John Barmby and his wife Frances of Kirstead Hall and for about a month before he enlisted into military service with Mr. Walter Herbert Garrard and his wife Annis Mahala.

On September 7, 1911, Ernest enlisted in the Norfolk Regiment. His age was listed on the enlistment document as 17 years, 11 months, just shy of his 18th birthday. He stood at 5 ft. 8-1/4 in. tall and weighing 130 lbs. With eyes of blue and light brown hair, he was probably considered a handsome fellow. But, Ernest was not without his faults. His minister said he was "rather abrupt and inclined to morass" It is not possible to understand what his minister meant by that, but Private Taylor's conduct sheet does have a long list of military infractions. The list includes:

15 May 1912 Carelessness on the rifle range -- 3 days camp confinement

3 Jun 1913 Inattention in the ranks -- 3 days camp confinement

25 Sep 1914 Absent from duty -- forfeiture 7 days pay

25 Sep 1914 Absent 7 days -- 7 days camp confinement

24 Oct 1914 Absent from duty -- 10 days camp confinement and forfeiture 5 days pay

14 Nov 1914 Overstaying his pass -- 10 days confined to barracks

30 Aug 1915 Dirty on Parade -- 2 days camp confinement.

The unit diary for the month of June 1916 is posted below to help understand what Private Taylor endured on a daily basis during the fighting in France.

[Note: I have written to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission to correct the record shown on it's website. The information shows that Private Ernest Edward Taylor, 3/7059, was attached to the 160th Company. However, his military record clearly shows this to be incorrect and resulted in not finding out the information provided in the 180th War Diaries. The War Diary is consistent with the death of Private Taylor on June 21, 1916.]

Private Ernest Edward Taylor, 3/7059, 7th Battalion,

Norfolk Regiment, attached 180th Tunneling Company, Royal Engineers. He died at Nord-Pas-de-Calais. Killed

in Action in France & Flanders on 21st June 1916 when helping to restore

parts of the British tunnels when a German mine exploded causing partial

collapse of the tunnel in which he was working. Aged 23. He

is buried in Vermelles British Cemetery, Pas de Calais, France. Ernest Edward Taylor was the second of three sons killed in the Great War.

Below is the link to the military record for Private Ernest Edward Taylor.

https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1219/images/31238_201306-00623?pId=1922249

Mine Warfare in the first World War.

During the First World War, the use of land mines referred

primarily to the digging of tunnels beneath enemy trenches and strongpoints,

and igniting large charges of explosive.

The use of mines in any capacity did not become an issue until

the end of 1914, when the mobility of the Battle of the Frontiers had broken

down, and impromptu fortifications appeared everywhere from Switzerland to the

English Channel. With the support of machine guns and artillery, even simple

earthworks became formidable defenses. Both sides looked to the available

technology for a tool that could assist in an attack on prepared defenses.

Explosives were the obvious answer; the question remained, however, of the best

way to deliver those explosives where they might have a telling effect.

In November, the possibility of having men carry small charges

to the enemy lines for a surface detonation was considered, but the digging of

tunnels below the target was soon found to be a more practical solution. The

practice of undermining an opponent’s walls had long been a feature of medieval

siege warfare, and in many respects, the static warfare of the Western Front

had come to resemble a medieval siege. Under these circumstances, many archaic

practices were revived, from the wearing of helmets and body armor to the use

of clubs. With the availability of modern explosives, the practice of mining

promised to be more effective than ever.

The greatest advantage over the placement of charges on the surface lay in the quantity of explosives that could be delivered. Men scurrying across No-Man’s Land by night could carry only a small charge, and even if it were placed perfectly, it could force only a small breach. A more carefully-prepared mine underground could allow for very large detonations. A single mine built underground could contain a massive collection of explosive material, with even 300 lbs of explosives rating as a small charge when compared with the larger mines in the war. Moreover, a given operation did not depend on the success of a single mine. Typically, a series of tunnels were dug under a fortified zone, and each was mined, with the intention of blowing all of them in a simultaneous wave of destruction.

Interestingly, considering their tactically defensive posture

for most of the war, it was the Germans who first used mines. They dug eleven

mines beneath a British-held position at Festubert, delivering mines up to 300

lbs in weight in each. They were ignited on December 20, 1914, and ten of them

exploded successfully. A brigade of Indian troops perished at once. For the

morale of their own troops, the British and French were compelled to invest in

the creation of teams capable of making their own mines.

In addition to the obvious offensive use of mines, this effort

also included the defensive practice of counter-mining. As the war progressed,

supporting devices like the geophone, enabling tunnelers to hear the approach

of enemy tunnelers as the mine drew near its intended target. Defenders sought

to foil enemy mines by building another mine beneath the attackers’ mine, and

then setting off a small explosive charge, called a camouflet, under it. The camouflet was much smaller than the

offensive mine, only being large enough to collapse the mine above it. In

practice, the effort was not always so straightforward. Frequently, the opposing sides would meet

unexpectedly, with a chaotic melee resulting.

It took some time for the French and British to catch up with

the Germans in their mining practices, but during the summer of 1916, the

Entente powers began to exceed the Germans. The French and the Germans used

mining extensively in the Vauquois section of the front, where in one blast the

Germans used sixty tons of Westfalit explosives on May 14. Eventually the

British exceeded both through the cultivation of specialists drawn from

professional miners. The hazards of operating in a war zone posed unfamiliar

challenges to those who had been miners in civilian life, and so it took some

time for these specialist units to prepare for their jobs, but once they had

acclimated themselves to the task, they were a formidable force. Armed with TNT

as their explosive of choice, British and other Dominion miners blew

devastating mines in the Somme and Ypres campaigns.

Besides all of the hazards faced by the miners themselves, from

cave-ins and toxic gases to enemy camouflets, the use of mines posed risks to

friendly soldiers above if the detonation of the mines were not adequately

coordinated with an attack. Ideally, the mines would blow at a time that would

permit the attacking force to reach the crater before enemy troops could rally,

and so a section of trench or a fortification could be seized. With poor

coordination, the enemy could send in reinforcements and hold a new zone of

difficult terrain before the attack arrived; or worse, friendly soldiers could

be killed in the explosion if it were ignited too late. Given all of these

elements, there was only one example of mining that proved strategically

decisive: the British mines under Messines Ridge in the Ypres campaign of 1917.

At Ypres, the mining was unusually extensive, with twelve separate tunnels being dug over the course of a year, one of them exceeding 2,000 feet in length. Twenty-one mines were laid, with the total weight of explosives approaching 500 tons. The charges were ignited on June 7, 1917, with nineteen of the mines exploding according to plan. An estimated ten thousand Germans were killed in blasts that could be heard as far away as southern England. Here, the British were able to claim the ridge and push the German line back.

The enormous underground mines of World War I had been a

response to static warfare, and the practice did not generally continue in

future wars, where battlefield mobility became a normal condition again. Like

the minefields of later wars, however, the mines of World War I sometimes

remained to pose a threat to future generations. Not all mines exploded as

planned, as seen in battles from Festubert to Messines Ridge. Of the two mines

at Ypres that failed to blow, one was triggered in 1955 as a storm raged in the

area.

Sources: Forty, Simon. World War I: A Visual Encyclopedia. PRC

Publishing, 2002

The War Diary of the 180th Tunneling Company

War Diary of 180th Tunneling

Company, Royal Engineers

14 June

1916 Germans sprung 2 mines south of the

existing series of craters at the QUARRIES (at 7 PM). Very slight damage done to underground

gallery at this point. No damage done on

surface to saps* or trenches. No

casualties above or underground.

15 June

1916 We sprung a mine of 2000 lbs. of

ammonal at the QUARRIES to destroy German underground gallery. The crater formed was among the existing

craters at this point and no damage was done to our saps or trenches. 50 ft. of tamping** was put in the LL R.

being small--running to existing craters-- at point mine was sprung.

16 June

1916 Germans sprung a mine at the

HAIRPIN at 7 pm – Mine was large one and destroyed about 50 ft. of

gallery. Crater formed was among

existing craters slightly on German side.

No damage to our saps. Casualties—one

man suffering from shock. No serious

casualties among Infantry.

17 June

1916 We sprung two mines at the HAIRPIN. The craters formed were among the existing

craters and no damage was done to our own saps.

The craters were in front of the right and left legs of the HAIRPIN

respectively.

The charges placed

were 2,000 lbs. and 3,000 lbs. ammonal with 70 ft. of tamping to help to save

the galleries. The object of the charges

was to destroy German galleries. In one

case, German gallery had been partially destroyed by German mine of 16 June

1916 and Germans were heard repairing it after their blow. It was therefore a suitable time to fire a

charge against it before the retimbering was complete. Germans working in it were probably caught.

19 June

1916 We sprung a mine of 2,000 lbs. of

ammonal at the HAIRPIN to destroy German galleries being driven alongside our

gallery. The crater formed was among the

existing craters. No damage was done to

our trenches or saps. The Germans were

heard working in their gallery immediately prior to the mine being sprung.

19 June

1916 The Germans spring a mine in the group

of craters at the QUARRIES. Very slight

damage was done to three of our galleries.

Slight fall of chalk and broken timber at ends. All them three galleries were being worked at

the time but no casualties were caused by the mine. No damage was done to our trenches and saps.

21 June

1916 The Germans sprung two small

mines at the QUARRIES damaging three galleries—20 ft –10 ft. and 12 ft.

respectively. No damage was done to

surface saps. Casualties underground. 2 O.R. [Other Ranks--not Officers]

killed. 3 O.R. wounded.

27 June

1916 We sprung a small mine of 1,000

lbs. of ammonal at the QUARRIES. The

charge was kept small owing to the closeness of the German gallery and the

proximity of another of our galleries.

28 June

1916 Mining was much interfered with

by Infantry raids and discharge of gas from our front line trenches. In addition to miners having to keep out of

mines in some cases, fatigue parties turned up irregularly. [relief personnel

were not showing up to replace tired workers on a regular basis.]

28 June

1916 Germans sprung a mine at the HAIRPIN

at the north end of the existing group of craters. Approximately 20 ft. of

gallery destroyed. No casualties as men

were being worked in this phase alternately with another.

Various Infantry

raids undertaken with assistance of gas and smoke clouds and fairly heavy

artillery bombardment. German

retaliation largely with trench mortars.

30 June

1916 Germans sprung a mine at the

HAIRPIN among the existing craters but well on their side and did very little

damage to our galleries.

We sprung two mins

at the HAIRPIN. One at north end and one

at south end of existing series of craters to destroy hostile galleries being

driven very close to ours.

Total number of

mines sprung by Company during month –13.

Total number of

mines sprung by Germans on Company front – 12.

Casualties during month –from mine explosions—killed 1 officer, 6 O.R.

–wounded 2 O.R.

from other causes in trenches, etc. – 44 wounded.

Billets –BEUVAY

Strength –

Officers -------------------------- 16

O.R. Royal Engineers ______375

Attached Infantry ------------- 269

V. E.

Buckingham, Major, Royal Engineers, Officer in Command, 180th Company,

Royal Engineers

*Saps: During the first World War,

a tactic used on the Western Front was to dig short trenches (saps)

across No Man's Land. These were dug towards the enemy trenches and enabled

soldiers to move forward without exposure to fire. Several saps would be dug

along a section of front-line.

**Tamping: Tamping is the

blocking of a charged shot hole with suitable stemming material, such as clay

tamping capsules. The purpose of tamping is to effectively contain and

distribute explosive energy in the blast hole. If tamping is not used, a great

deal of blast energy is lost, resulting in a poor blast.

Comments

Post a Comment