Heroes and Rebels in the Family Tree -- Robert Jeremiah Wooltorton

Heroes

and Rebels in the Family Tree – Robert Jeremiah Wooltorton

Military Service:

By the time he reached the age of 18, he enlisted in the Royal Regimental Artillery at Colchester on June 22, 1885, Reg. No. 49410, and was promoted to the rank of Corporal in 1889. He was reduced in rank to Bombardier in a Courts Martial on January 22, 1893 for “Conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline in that, he at Woolwich on the 22nd January 1893, reported to the company Sergeant Major McGowan, R.A., Regimental District Staff, that Sergeant E. Stoyle was absent on pass from Church Parade, the prisoner well knowing such statement was false.” By 1896 he earned back his promotion to Corporal and then to Sergeant in 1897. In 1904, he was again promoted to Company Quartermaster Sergeant (CQMS). In this position, he served as the deputy to the company Sergeant Major and is the second most senior Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO) in the company. During his 21 years of military service prior to the start of World War I, he had completed tours in England and Malta. Robert Jeremiah was discharged from service on June 16, 1906. However, retirement didn’t last long for this patriotic man. On October 19, 1914, he enlisted again for service in the Royal Regimental Artillery and was reinstated to his previous rank as the Acting Company Quartermaster Sergeant where he performed draft conducting duties for soldiers departing for the war in France. He continued in that role until his discharge on June 8, 1915 when his services were no longer required.

Family Life:

Four years after his initial enlistment in the Royal Regimental Artillery, Jeremiah met and fell in love with Alice Ann Brown. They were initially married at the Parish Church in Paulerspury, Northamptonshire, England on December 18, 1889 witnessed by William Brown and Susannah (Susan) Brown—Alice’s older siblings. For some unknown reason, they were re-married at St. John’s Church, Woolwich, London, England on August 29, 1892. Jeremiah’s younger half-brother Frederick Wooltorton and Alice’s older sister Susan Brown were witness to the second marriage. Perhaps, the military required permission for marriages in order to provide family pay allowance, housing and travel authority and the second ceremony was required to fulfill military protocol.

While stationed at the Royal Regimental Artillery training base at Woolwich, Jeremiah and Alice had their first child Dorothy Alice Wooltorton, born on July 14, 1893. Katie Bona Wooltorton soon followed and was born in Woolwich on February 9, 1895. By 1899, the family was relocated to Ireland. Violet Kathleen Wooltorton was born on November 18, 1899 at Fort Westmoreland, County Cork, Ireland. Today, Fort Westmoreland is known as Spike Island and the fort was repatriated to Ireland in 1938 and renamed Fort Mitchel.

On March 5, 1901, Jeremiah, together with his wife and three children, boarded the transport ship “Wakool” for their new assignment in Malta. This tour would last 4-1/2 years and during that time his fourth child, Robert William Christian Wooltorton was born in Malta on November 16, 1903. By 1906, he was nearing the end of his 21 years of service when his fifth child, Mark Sydney Cecil Wooltorton was born in Plymouth, Devon, England on May 17, 1906.

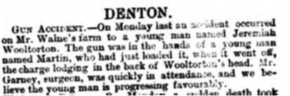

Extraordinary

as it may seem, Robert Jeremiah, in spite of growing up in poverty, being shot

as a young lad, serving in the military for 21 years and serving again at the

start of World War I in order to train many raw recruits to give them the skills

necessary to survive on the battlefields of France, lived to a grand old age

and, in 1954, he and his wife were able to celebrate 65 years of marriage! An

extraordinary achievement, the couple had married when they were 22 and 21

years old respectively and raised 5 children as they toured the world in his 21

years of military service. This tough old soldier lasted just over another 2

years and died in 1957 aged 89.

An Extraordinary Athlete:

After leaving the Army,

the pensioner had a number of jobs although he remined local. He must have been

extraordinarily fit; when he was the landlord of The Buck Inn at Flixton, for a

bet, he undertook to swim the 1912 flood waters from the Norfolk side of the

River Waveney over to his pub. This epic and extraordinarily dangerous swim

took almost 3 ½ hours. He had been an Army Athlete, a licensed victualler (having

been trained in military cooking school), was known locally as the Strawberry

King due to his success in growing and selling his produce and finally had been

a professional destroyer of rabbits. According to the Diss Express article

published on December 24, 1954, Robert Jeremiah was an extraordinary

athlete.

“During his long service career, Mr.

Wooltorton, in his first year, became champion runner of a garrison in the

Eastern Counties, and was a miler of outstanding merit. ‘Jerry’ as he is affectionately known to many

in the district dryly commented, ‘Of course, my time for the mile was slightly

more than Bannister’s.’ He was

afterwards champion runner of another garrison for three years and had never

been beaten in obstacle races.

“At a military exhibition he won the

obstacle race against all-comers from various regiments. Later he took up cycling, and, in 1892 became

an Army cyclist champion. On his

discharge from the army in June 1906 he held the rank of Company Quartermaster

Sergeant. He volunteered for service in

the first world war and in addition to serving in France did much valuable

training work at home.

“For twelve years Mr. Wooltorton was

employed as a warrener at Pulham Mary Hall and other local farms, and in one

season alone accounted for more than 1,000 rabbits. He admitted that at that time he had no knowledge

of the now prevalent myxomatosis disease.”

An Interesting Life,

Indeed:

(Robert) Jeremiah received a wound to his

head in his youth which occasionally led to episodes of confusion. Still, he

was a tough fellow and in 1934, at the age of 67 he cycled from Harleston to

Diss, slipped on the steps outside the Star after having had a pint of beer and

became very confused. This confusion lasted some hours to the extent one of his

sons had to fetch him by car; unfortunately, a policeman came across the former

soldier, smelt the beer, noted the disorientation and assumed he was drunk.

Now, in his youth Jeremiah had been an occasional boozer (but I suspect no

worse than most of this peers) but on this occasion, Superintendent Fuller

spoke up for him in court and he was discharged with a warning! Most unusual

but the court case did reveal that Jeremiah and his 4 military brothers had all

achieved the Rank of Regimental Sergeant Major or Colour Sergeant.

On another occasion,

the brothers James, George, Jeremiah and oldest brother William Sheldrake along

with a friend James Websdale got themselves absolutely plastered when Jeremiah

was on leave from the Army.

The Ipswich

Journal published its account of the case on September 27, 1889:

“Unfortunately,

Jeremiah, having been initially arrested, was promptly ‘rescued’ from the

police by the rest of his party and was later heard swearing that it would need

40 men to take him! Dear old mother, widow Hannah Wooltorton, gave her son

Jeremiah an alibi for the occasion, stating that at the time he was accused of

carousing around Bungay with his wing men, he was actually with her ‘In defence

the prisoner (Hannah Wooltorton) said they were all against her, it was

no good her saying anything she had no witnesses. The court decided she was to

be sent to the next assizes. Shame on you boys!”

FOOTNOTE: About Dr. Barnado’s Home for Boys and Girls

Beginnings – the Ragged School

|

| Thomas Barnardo at his desk |

Thomas John Barnardo was born in Ireland 1845. As a young man he moved to London to train as a doctor. When he arrived, he was shocked to find children living in terrible conditions, with no access to education. Poverty and disease were so widespread that one in five children died before their fifth birthday. When a cholera epidemic swept through the East End, leaving 3000 people dead and many orphaned children, the young Barnardo felt an urgent need to help

His

first step, in 1867, was to set up a ‘ragged school’ where children could get a

free basic education. One evening a boy at the mission, Jim Jarvis, took

Barnardo around the East End, showing him children sleeping on roofs and in

gutters. What he saw affected him so deeply he decided to abandon his medical

training and devote himself to helping children living in poverty.

|

| Barnardo's children in 1906 |

No

child should be turned away

In

1870, Barnardo opened his first home for boys. As well as putting a roof over

their heads, the home trained the boys in carpentry, metalwork and shoemaking,

and found apprenticeships for them.

To

begin with, there was a limit to the number of boys who could stay there. But

when an 11-year-old boy was found dead — of malnutrition and exposure — two

days after being told the shelter was full, Barnardo vowed never to turn

another child away.

Barnardo’s

work was radical. The Victorians saw poverty as shameful, and the result of

laziness or vice. But Barnardo refused to discriminate between the ‘deserving’

and ‘undeserving’ poor. He accepted all children, regardless of

race, disability or circumstance.

Barnardo

believed that every child deserved the best possible start in life, whatever

their background. This philosophy still guides the charity today.

Barnardo’s

girls’ village

In

1873 Barnardo married Syrie Louise Elmslie, who was to play an important role

in the development of the charity. As a wedding present, they were given a

lease on a 60-acre site in Barkingside, east London, where the couple opened a

home for girls.

|

| Barkingside village in the 1900s |

Syrie

was especially keen to support girls who had been driven to prostitution.

Protecting children from sexual exploitation continues to be an important part

of our work today.

The

Barnardos were early adopters of the ‘cottage homes’ model. They believed that

children could be best supported if they were living in small, family-style

groups looked after by a house ‘mother’.

By

1900 the Barkingside ‘garden village’ had 65 cottages, a school, a hospital and

a church, and provided a home – and training – to 1500 girls.

Caring

for more and more children

Barnardo

went on to found many more children’s homes. By the time he died in 1905, the

charity had 96 homes caring for more than 8,500 vulnerable children. This

included children with physical and learning difficulties. Barnardo’s

experience of caring for his daughter Marjorie, who had Down’s syndrome,

strongly influenced his approach to the care of disabled children.

Comments

Post a Comment