Heroes and Rebels in the Family Tree--William Wright and the Steamship Elbe Disaster

1. Harriet Gertrude Wright (1882-1972) married William Robert Girling.

2. William George Wright (1884-1885).

3. Bertie William Wright (1886-1911)

4. Ethel Maud Wright (1888- )

5. Girl (name uncertain) Wright (1889- )

6. Florence Ada Wright (1891-1973) married Charles Edward Baxter.

7. Charles William “Willie” Wright (1895- ).

8. Florence May Wright (1898-2005) married Frederick G. Hindes and died at age 107.

By 1895, William Wright was the skipper for the fishing Vessel "Wild Flower" (LT557) owned by George Lond. It was on this vessel that William Wright was able to rescue 22 persons from a sunken ship and for this heroic action, he became an instant celebrity in his hometown and throughout the world.

William Wright becomes an International Hero.

The night of 30 January 1895 was stormy. In the North Sea, conditions were freezing and there were huge seas. The Steamship Elbe had left Bremerhaven for New York earlier in the day with 354 passengers aboard. Also at sea on this rough night was the steamship Crathie, sailing from Aberdeen in Scotland, heading for Rotterdam. As conditions grew worse, the Elbe discharged warning rockets to alert other ships to her presence. The Crathie either did not see the warning rockets or chose to ignore them. She did not alter her course, and she struck the liner on her port side with such force that whole compartments of the Elbe were immediately flooded. The collision happened at 5.30 am and most of the passengers were still asleep. The Elbe began to sink immediately and the captain, von Goessel, gave the order to abandon ship. Amid great scenes of panic the crew managed to lower two of the Elbe's lifeboats. One of the lifeboats capsized as too many passengers tried in vain to squeeze into the boat. Twenty people scrambled into the second lifeboat, of whom 15 were members of the crew. The others were four male second-class passengers and a young lady's maid by the name of Anna Boecker, who had been lucky enough to be pulled from the raging sea after the first boat had capsized.

Things looked bleak; the Elbe's distress rockets had not been seen by any passing vessels and so no one knew of their predicament. After five hours in the raging storm, their luck changed. A fishing smack from Lowestoft called the Wildflower found them. In desperate conditions the crew of the Wildflower struggled to pull the 20 survivors from the lifeboat, which had begun to break up. The skipper, William Wright, said later that the survivors would not have lasted another hour in those conditions, and believed that the only reason they had stayed alive for five hours was the expertise of the Elbe's crewmen aboard the lifeboat.

Genealogy: William Wright (1863- ) married Mary Elizabeth Mewse (1862- ). Her mother was Mary Ann Barnaby (1839-1905) and her mother was Elizabeth Welch (1812-1879) and her father was Charles Welch (1770-1859) and his father was Charles Welch (1743-1783) and his father was Charles Welch (1716-1765) and his brother was Thomas Welch ( -1746) and his son was John Welch (1735-1802) and his son was Thomas Welch (1761-1792) and his son was John Welch (1787-1884) and his son was John Welch 1812-1884) and his daughter was Susannah Welsh (1847-1898) and Susannah Welsh had a son named George “Pikey” William Welch-Adams (1867-1940).

For more information on the sinking of the Steamship Elbe and the aftermath, continue reading the accounts as published in the newspapers as soon as news of the disaster was made known.

The

Queenslander (Brisbane,

Queensland) Saturday, 23 March 1895

Loss of the Steamer Elbe,

PARTICULARS BY AMERICAN

MAIL.

FOUNDERED IN TWENTY

MINUTES.

344 LIVES LOST.

(Abridged from the

Philadelphia Ledger.)

London, January 30.

The North German Lloyd steamship Elbe, bound

from Bremen for New York, sank at 6

o'clock this morning after colliding with a small steamer in the North Sea,

fifty miles off Lowestoft. She carried 240 passengers and 160 officers and

seamen. Twenty-two survivors of the wreck have been landed, and a few others

may still be afloat in a lifeboat. All the others were lost. Captain Von Goessel

went down with his ship.

|

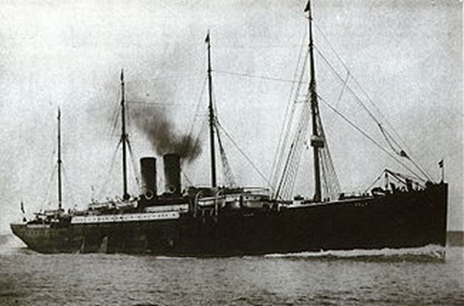

| The Steamship Elbe |

The twenty-two survivors were landed at Lowestoft at 5.40 o'clock this evening by the

fishing smack Wild Flower.

The passengers were but half-clothed.

Their few garments were frozen stiff, their hair was coated with ice, and

anxiety and effort had exhausted them so completely that they had to be helped

ashore. The officers and sailors were fully dressed, but their clothes had been

drenched and frozen, and they had been almost paralysed with cold and fatigue.

They had been ashore three hours before they had recovered sufficiently to tell

the story of the wreck. Their accounts agreed upon the following points: —

The Elbe left Bremen on Tuesday afternoon. The

few hours of the voyage before the disaster were uneventful. At 4 o'olock this morning

the wind was blowing very hard and a tremendous sea was running. The morning

was unusually dark. Numerous lights were seen in all directions, showing that

many vessels were near by. The captain ordered, therefore, that rockets should

be sent up at regular intervals to warn the craft to keep out of the Elbe's

course. It was near to 6 o'clock, and the Elbe was some fifty miles off

Lowestoft, coast of Suffolk, when the lookout man sighted a steamer of about

1500 tons approaching. He gave the word, and, as a precaution, the number of

rockets was doubled, and they were sent up at short intervals. The warning was

without effect. The steamer came on with unchecked speed, and before the Elbe

could change her coarse or reduce her speed noticeably there was the terrific

crash of the collision. The Elbe was hit about her engine-room. When the small steamer

wrenched away an enormous hole was left in the Elbe's side. The water poured through and down into the

engine-room in a cataract. The room filled almost instantly. The engines were still and the big

hulk began to settle.

The passengers were in bed. The bitter cold

and rough sea had prevented any early rising, and none except the officers and crew on duty were on deck when the

ship was struck. The shock and crash roused everybody. The steerage was in a

panic in a moment, and men, women, and children, half-dressed or in their night

clothes, came crowding up the companion-ways. They had heard the sound of

rushing water as the other steamer backed off, and had felt the Elbe lurch and

settle. They had grasped the fact that it was then life or death with them,

and, almost to a man, had succumbed to their terror. They clung together in

groups, facing the cold and storm, and cried aloud for help or prayed on their

knees for deliverance. The officers and crew were calm.

For a few moments they went among the terror-stricken

groups trying to quiet them, and encouraging them to hope that the vessel might

be saved. It was soon apparent, however, that the Elbe was settling steadily.

The officers were convinced that she was about to founder, and gave orders to

lower the boats.

In a short time three boats were got alongside,

but the seas were breaking over the steamer with great force, and the first

boat was swamped before anybody could get into it. The other two boats, lowered

at about the same time, wore filled quickly with members of the crew and some

passengers, but the number was small, as the boats held only twenty persons each.

The boat carrying the twenty-one persons who

were landed at Lowestoft put off in such

haste from the sinking steamer that nobody in it noticed what became of the

other boat. The

survivors believe, however, that she got away safely. They say that they tossed

about in the

heavy seas for several hours before they sighted the Wild Flower. The little

smack bore down on them at once, and took them aboard. They were exhausted from

excitement and exposure. Several of them were in a state of collapse, and had

to be carried and dragged from one boat to the other.

Miss Anna Buecker, the only woman in the party, was prostrated as soon as they got clear of the Elbe. She lay in the bottom of the boat for five hours with the seas breaking over her, and the water that had been shipped half covering her body. Although her physical strength was gone she showed true pluck, however, and did not utter a word of complaint, and repeatedly urged her companions not to mind her but look after themselves.

Carl Hofmann, who came ashore in the Wild Flower,

said in an interview:—

“I am abroad to visit relatives in Germany, and

during the last four months was accompanied by my wife and boy. We left Bremen for

home on Tuesday. I was asleep in our stateroom when a noise like a gunshot woke

me. I jumped out of bed and spoke to my wife, who had been aroused as suddenly.

I hurried into a few of my clothes, however, and went to the upper deck. I saw

only too dearly then what had happened. I rushed below and helped my wife and

boy throw on a few clothes and we went on deck together. The excitement and

confusion cannot be described. I never saw anything like it; everybody seemed to

have lost his head. Men, women, and children were running about madly, the

women screaming with terror and every man getting in the other's way. The

darkness increased the confusion and fright. Suddenly I heard shrill, despairing

cries from the women, ‘There are no more boats.' I then saw the men at the davits.

I noticed that the ropes were frozen so hard or were so tangled, or something

of the sort, that the sailors had to chop them frantically to get the boats

clear. The sailors were doing their best, however, and worked with might and

main. They finally got out the aft-quarter boat on the port side. I could see

that it was full of people, but the sailors could not lower it.

“Meanwhile the steamer was settling perceptibly.

I took my boy in my arms and got into the second boat. My wife was close behind

when somebody shouted, 'All women and children go on the other side of the

ship.' I believe the captain gave the order. My wife started to run across the

deck, and that is the last I saw of her. I clung to my boy, but some men seized

us and dragged us out of the boat, and my place was taken by one of the crew.

“This boat got clear of the steamer. Before the

men at the oars could get fall command of

her a big wave almost dashed her against the steamer's foremast, which had gone

by the board at the time of the collision. It was almost miraculous that the

boat was not swamped. Another boat was got out. I took my boy into it and

supposed that he had remained by my side, but just as the boat was lowered I

found that he had disappeared. He had been torn away in the rush and scramble

for places. I tried to get back, but the boat went down with a jump, and the moment

we reached the water the sailors pushed off."

Another survivor said:— “I asked if I should

get into a lifeboat, and was told to keep out, as the women and children must

go first. I saw that the struggle for the lifeboats was too desperate to leave

a man much chance, so I waited and looked on. The men round me had grown

frantic. They tried to tear off my life preservers, but I shouldered them off.

Meantime other men had begun to climb into the boats, and I realised that I must

take my chance then or not at all. I jumped on the rail as a boat sheered off,

and, when the boat rose on a wave, I jumped in. One of the occupants tried to

shove me out, but I hung to him like death, thinking 'if I go, you go too,

old man.' He seemed to understand this after he felt my grip a few times, and

let me stay.

We saw the Elbe sink, and cruised about half-full of salt water until the Wild

Flower rescued us."

Third Officer Stolberg says that he cannot explain

the collision, and that it is unlikely

that any adequate account can be obtained, as all the deck watch on duty at the

time were drowned. The captain was on the bridge when the collision occurred,

and Officer Stolberg heard him shouting in a loud, firm voice that the women

and children were to be saved first. The captain's voice reached a considerable

distance. His order was repeated by the chief officer, and must have been heard

by everybody aboard.

Officer Stolberg expressed the warmest

gratitude to Skipper Wright and the crew of the Wild Flower. The roughness of

the sea, he said, made the work of rescue extremely perilous. The fishermen

gave the survivors use of everything aboard the smack, and fed and clothed

them. There is some hope that the missing boat has been rescued, inasmuch as

there were several smacks in the vicinity of the collision. Probably some women

and children got into the missing boat.

The Elbe carried ten lifeboats and twelve collapsable

boats, besides four liferafts. The accident, he thought, must have occurred in

a fog, and that immediately after the collision the colliding steamers must

have lost sight of each other. The first duty at such a time is to look out for

oneself, and doubtless the other steamer, being in a leaking condition, made

for the nearest port.

FURTHER PARTICULARS.

London, February 3.

The owner at Aberdeen of the steamship

Crathie, which ran into and sank the Elbe, has received a brief telegram from the captain at Maasluis, stating that the

Crathie's bow was terribly crushed by the impact of the vessel with the Elbe, and that the

Crathie was in a sinking condition when she reached Maasluis. The captain was

below at the time of the collision, the mate being in charge of the vessel. The

latter has made a statement to the captain that he has no knowledge whatever as

to the identity of the vessel with which the Crathie collided. His own vessel was

so terribly damaged that its condition called for the undivided attention of the

officers and the entire crew, all of whom had to bend their energies to saving

their ship and their own lives. There was, the mate adds, a dense fog at the

time of the accident, and the vessel with which the Crathie had collided was

lost to view in the mist almost immediately after the crash.

Mr. Carl Hofmann, of Grand Island, Nebraska, who is among the saved, refutes this statement by making the assertion, in addition to his statement already published, that if the vessel which came into collision with the Elbe had stood by the sinking ship a majority of her passengers might have been saved, as the Elbe stood perfectly still for many minutes after the impact. In fact, she remained motionless until the water which was pouring into her hold caused her to lurch violently, after which all was confusion on board. Prior to this, however, discipline was maintained, and there could have been no difficulty in transferring the passengers in an orderly manner.

The survivors who were brought to Lowestoft are all recovering from the effect of their shock and exposure. Miss Anna Boecker, the only woman known to have been saved, has so far recovered that she will be able to proceed to Southampton today.

The surviving officers of the Elbe are very reticent in regard to the disaster, reserving their statements pending an official inquiry into the circumstances, but it transpires that an officer of the Elbe saw a green light on the port bow belonging to an unknown vessel, which, it is alleged, was trying to cut across the Elbe's bows. This light evidently belonged to the Crathie.

A despatch to Lloyd's from Rotterdam says the Crathie left Maasluis at 10 o'clock on the night of 29th January for Aberdeen, and returned to Maasluis at 1.25 p.m., 30th January, damaged. She reported having been in collision with a large unknown steamer, which her officers thought was probably an American liner. The Crathie's stern was completely gone above the water line, having been carried away by the third frame, but she was perfectly tight and had made no water. The collision, according to the officers of the Crathie, occurred between 5 and 6 o'clock on the morning of 30th January. One of the crew of the Crathie was injured by the collision.

The lifeboat of the life-saving station at Ramsgate has returned after being out fifteen hours searching for possible survivors of the Elbe, but found no trace of either boat or wreckage. The Broadstairs lifeboat also returned this morning. Upon nearing the station the boat was blown ashore by the violent gale, and the crew were dashed into the surf. Several of them were injured. A blinding snowstorm is raging at the mouth of the Thames, and navigation is suspended.

A tremendous wind, heavy sea, and blinding snowstorm drove the tug Despatch back to Lowestoft at noon today, after she had proceeded only a short distance to search for survivors of the Elbe. The storm moderated somewhat after her return, and in the afternoon she started again.

STATEMENT OF THE ENGLISH PILOT.

Greenham, the English pilot on the Elbe, who was one of the survivors, said, in the coarse of an interview: —

“When I came on the deck of the Elbe the captain was in charge. The first order given was, ‘Swing the boats out; don't lower.’ The next was, ‘Everybody on deck; crew to their stations.' This was followed by 'Women and children to the starboard boats, to be saved first.'

“These orders were given by the captain himself, and were repeated by the chief officer. The next order was, 'Lower the boats.' There was no confusion whatever among the crew or in the giving of orders, nor was there any panic among the passengers. A high sea was running, and there was a strong east-south-east wind. There had been an average of 19deg. below the freezing point since the morning. The lanyards of the boat-grips were frozen, and were chopped away in order to save time. The ship went down two minutes after we left her."

THE 'WILDFLOWER' WORK OF RESCUE.

William Wright, the skipper of the fishing smack Wildflower, says:—" We were east south-east of Lowestoft with out trawling gear down when, about 11 o'clock yesterday morning, I saw a ship's lifeboat a mile away. The boat's mast was naked, but I saw something fluttering from her stern. The water was breaking over the boat. I watched the boat closely. Her occupants seemed to think I was going to leave them, so I waved my hat. It took us half-an-hour to get up our trawling gear, and in the meantime the boat was drifting away from us. When we got close to them I cast them a rope, but they were so cold, wet, and numb, that they could not make it fast for some time. We pulled them around to the side of the smack, and about half of them jumped overboard, but the strain caused by the heavy sea parted the rope, and the remainder once more drifted away. Eventually we made another line fast, and four more of the unfortunates were dragged in, leaving a woman and four men in the boat.

“The woman lay in the water in the bottom of the boat. She wore a long coat, but had on no neither boots nor dress. Pilot Greenham helped her to get on board the smack. Just as all had boarded the smack the line again parted and the lifeboat was lost. I got the woman below, and asked all the others to go to the engine-room while she took off her clothes and wrapped herself in dry blankets. I am sure another hour's exposure in the boat would have killed some of them, for there was 6 in. of ice on my deck."

WHY THE CRATHIE DID NOT STAND BY.

Steerage Passenger Bothen says that after the strange vessel struck the Elbe she sheered off and steamed in a semicircle around (he Elbe, but did not come near her, though had she done so she could have rescued a large number of those on board the sinking ship.

A despatch from Rotterdam to a London news agency says:—"Captain Gordon, of the steamer Crathie, says the steamer with which his ship came into collision was lost sight of immediately after the vessels came together, and it was thought she had proceeded. The Crathie remained in the vicinity for two hours and then returned to Rotterdam, as it was feared that she could not keep afloat."

“A TERRIFIC RUSH FOR LIFE.”

When questioned this evening as to the conduct of the crew after the collision, all the survivors of the Elbe wreck agreed that the officers and seamen were very cool and self possessed.

Eugene Schlegel, a second cabin passenger on the Elbe, said:— "When I was wakened by the crash I jumped from my berth and found myself knee-deep in water. It took me ten minutes to find my sister. When the women and children were ordered to the starboard side of the boat I led my sister across. The women were crowded together near the rail, shrieking and crying. The crew seemed to be working with perfect discipline. I saw one boat filled with passengers, and believe it cleared the ship, I left my sister to go back to the port side, and I did not see her again."

A DENIAL THAT THERE WAS FOG.

The surviving officers of the Elbe denounce the fog story of the Crathie's officers as pure invention. The English pilot, Greenham, said:— "lt is a black lie. There was no fog. It was quite clear, and the lights of several smacks were visible four or five miles off." The Elbe seamen made similar statements.

MISS BOECKER'S STORY.

Miss Boecker has been interviewed a dozen times today, despite the nervous reaction following her experience yesterday. She speaks English fluently, and does not tire of telling her story to the English reporters. She says that she is an orphan, 20 years, had been visiting relatives in Bremen, and was returning via Southampton to Portsmouth, where she earns her living aa a lady’s companion.

"As the trip was so short I did not undress, but lay down in my berth with my clothes on. I was sleeping lightly when the crash came. Somebody was at my door almost immediately, calling to me that I must get ready to leave the ship. I put on my hat and jacket, took my watch and money in my belt, and joined the other cabin passengers, who were rushing for the deck. I could see that the ship was sinking. A lifeboat near me was being got ready, and two men who had helped me in the crowd put me in it. As soon as the boat reached the water it began to fill. I did not notice any waves washing over, and I believe the water came from the plughole in the bottom, but do not know. As the boat sank the other persons in it grasped the side of the ship, which had settled almost to a level with the water. They clambered up to the deck, but I could only cling to the Elbe's rail. After two or three minutes another lifeboat was launched. I worked my way along the side of the ship and grasped one of the oars. A sailor palled me in with great difficulty and laid me in the bottom of the boat. I had been in the water about ten minutes and was almost paralysed. I did not see anybody else in the water, and the roaring of the wind and waves prevented my hearing the cries of the perishing. As I was flat on the bottom of the boat I could not see the Elbe go down, but the men in the boat told me when the end came. The waves swept over the gunwale of the boat continually, so the men could not stop bailing for a minute. There was no rest for them from the time we left the steamship until we boarded the WildFlower."

London, February 1.

Six fishing smacks returned to Lowestoft during last night. They were trawling in the vicinity of the disaster to the Elbe, but saw no boats or wreckage. The wind abated somewhat this morning, but the snow is still falling and the sea is very high.

Vevers, Hoffmann, and Schlegel, survivors, denied emphatically this evening that the Crathie remained signalling for two hours near the scene of the collision. They say that had she done so she could have saved many lives. Hoffmann, who was among the first to reach the Elbe's deck after the collision, did not see the Crathie answer any of the Elbe's signals. He noticed a small steamer, apparently the one that struck the Elbe, steaming away.

As regards the behaviour of the Elbe's crew, Hoffmann says:— "I seized a lifebelt as soon as I got on deck, but a sailor demanded it, saying that it belonged to the crew. I gave it up with the remark, 'Well, I hope you will save yourself,' but he did not. The crew did their best to keep the passengers out of the boats."

Hoffmann was greatly embittered by the loss of his wife and child. He talks continually about it, and in each interview makes new charges against the crew.

"I was born among the Indians out West.' he said this afternoon. "I have gone through rough times with my family there. Now it is all over with them, and they have been sacrificed by the carelessness of these men. I do not value my own life now; I can think only of my loss."

Hoffmann's description of the final settling of the ship was vivid: "I could see her sinking rapidly as we pulled away in the small boat. Her bow went steadily into the air. The deck grew steeper, and I could see the poor wretches aboard her climbing and crawling towards the prow, until suddenly all were engulfed."

Vevers told a

reporter tonight: "There were a lot

of green hands in charge of the lifeboats.

They were so excited they did not know what they were about. They filled one boat and then dumped all the occupants into the water. The crew in our boat were very reluctant to admit Miss Boecker. Hoffmann and I dragged her in without any aid from the seamen."

Vevers and Hoffmann also attack Third Officer Stolberg and First Engineer Neussel. They say that both acted selfishly after the rescue, and that Stolberg made no effort to command the boat, but gave the whole responsibility to the steerage passenger, Boethen, who had been cook on a French steamer. They speak highly of Boethen's coolness and skill, and give him the whole credit for managing the boat.”

Many more smacks arrived at Lowestoft late this afternoon and this evening. They brought no news. Others are due to arrive to-morrow and Sunday.

The skipper of the smack Competitor, which returned tonight, reported that he saw yesterday what he thought was a mail bag, and tried to catch it with a boathook. He missed it, and, knowing nothing of the collision, did not try for it again.

The Shipwrecked Mariners' Society has sent a barometer to Skipper Wright, of the Wild Flower, and £10 to his men, and the Mayor of Lowestoft has opened a fund for their benefit.

The Elbe lies in twenty-one fathoms of water. The thermometer was 19deg. below the freezing point when she left Bremen. This accounts for the condition of the tackle at the time of the accident. Hoffman lost £100 and Schlegel £90, besides all their clothes.

New York, February 1.

The North German Lloyd's agency in this city today received a cable despatch from the home office in Berlin which gives the exact number of persons who were on the ill-fated steamship Elbe as follows:—-Cabin passengers to New York, 44; Cabin passengers for Southampton, 6; steerage passengers for New York, 139; steerage passengers for Southampton, 10; captain and crew, 146; postmen, 4; stewardesses, 3. Two pilots were also aboard the vessel, making 354 persons in all. Of these 20 were saved. Total loss of life, 334 persons.

THE CRATHIE SEIZED.

Rotterdam, February 1.

The North German

Lloyd Steamship Company, owners of the lost steamer Elbe, have arrested the

British steamer Crathie by nailing a writ to her mast. This action is taken

preliminary to claiming damages for the sinking of the Elbe by the Crathie. The

Crathie is worth £8000 without her cargo. Captain Gordon, of the steamer

Crathie, has made a report to the Lloyd's representative,

in which he says that he was knocked down by the shock of

the collision of his ship with what he describes as an unknown vessel. When he

was able to get up and reach the deck the ships were some distance apart, and in

consequence he is unable to give much information in regard to the circumstances

or result of the disaster. The vessel which the Crathie struck, he says, was a

big steamer with two funnels and four masts. In reply to the question whether

he had taken any steps

to save the passengers and crew of the other ship, Captain

Gordon said his own ship was damaged to such an extent that he expected every

minute she would sink. He followed the other ship for a short time, but found

that she went much faster than the Crathie, and, therefore, he thought she was

safe.

|

| Depiction of the Trawler Wildflower rescuing passengers and crew from the lifeboat from the Steamer Elbe. Painted by George Vemply Burwood |

The SS Elbe incident resulted in a court case which took place in Rotterdam in November 1895. The court found that the steamship Crathie was alone at fault for the collision. Amazingly the captain was merely censured for leaving the disaster, a verdict that astounded the maritime world at the time. The blame was put squarely on the first mate, who had left his post at the bridge at the critical time to chat in the galley with other crew members, and therefore had failed in his job of operating the ship's warning lights. The captain, officers and sailors of the SS Elbe received no rebuke from the court either, which caused some concern amongst the German public. The crew of the fishing smack Wildflower each were given, by Kaiser Wilhelm II, a silver and gold watch bearing his monogram and £5 as a gesture of thanks for saving the lives of the eighteen German citizens, an Austrian, and the English pilot. They also received other medals and gifts in the following years.

THE

ELBE DISASTER.

FINDINGS

OF THE ADMIRALTY COURT.

The Mate

of the Crathie Held to Be Mainly Responslble for the Awful Collision--Officer

In Charge of the Elbe Was Not Entirely Blameless.

Bremer Haven,

Aug. 13, -- The admiralty court has rendered a decision to inquiry made

into the sinking of the North German Lloyd steamship Elbe, in collision with

the British steamer Crathie, in January last. The court holds that the blame

for the collision must be attributed to the mate of the Crathie, who deserted

his post immediately before the occurrence and went into the galley of the

Crathie, but says the officer in charge of the watch of the Elbe cannot,

however, be freed from the reproach that he omitted to get out of the way of

the Crathie by a timely manipulation of the helm, and failed to attract the

attention of the crew of the Crathie by signaling with the steam whistle.

In regard to the

steps taken to save life on board the Elbe, after the collision occurred, the

court holds that the orders given by Captain Van Gosset, and executed by the

officers and crew of the Elbe for that purpose, were deserving of praise.

As to the

suddenness with which the Elbe foundered, the finding of the court says that it

was not attributable to defects in her construction, lack of seaworthiness or

defects in the equipment, loading or manning of the vessel, but solely on

account of the damage occurring, which extended to the water-tight compartments

amidships, so that two of its divisions were flooded.

As to the

allegations made against the commander of the Crathie, the admiralty court

finds no ground for censuring him or the other navigators of the Crathie; in

regard to their omitted attempts to save life after the collision, as the

Crathie, according to the findings, suffered such severe injuries that there

was justifiable fear that she herself would founder. In conclusion, the court

finds that the conduct of the survivors of the crew of the Elbe who were

rescued by the British fishing smack Wild Flower, from an open boat, is

deserving of recognition, and that the rescue of people by the Wild Flower

merits the highest praise.

Comments

Post a Comment