Heroes and Rebels in the Family Tree—James John Dowsing, the unintentional emigrant.

By the age of 25, James had

not married.

On November 3, 1801,

James was accused in Poultry, London, England of stealing a parcel of cloth out

of a cart and was arrested. He was subsequently charged on December 2, 1801 with

Grand Larceny theft because of the value of the items stolen.

Here is a report of the

trial as published:

JAMES DOWSING was indicted for feloniously stealing, on the

3d of November, a wrapper, value 1s. and thirty-five yards of woollen cloth,

value £11. 4s. the property of William Sutton.

WILLIAM SUTTON sworn. - I keep the Salisbury Arms,

in Cow-lane, Smithfield: On Tuesday, the 3d of November, I sent a truss of

goods to Chester's-quay, by William Woodlands, directed to Henry Braden, of

Canterbury.

WILLIAM WOODLANDS sworn. - I am porter to Mr.

Sutton: On the 3d of November, as I was coming into the Old Jewry, I missed a

truss of goods out of the cart; I was in the cart, driving with a rein, when I

missed the good; I turned my horse round to go

towards Coleman-street, and saw a man on the other side of the way, with a

truss of goods on his shoulder; I met him coming towards me with it; I cried

out, stop thief, turned my cart round again, and soon overtook him; he was in

custody of an officer when I came up.

Q. When you say you met a man with a truss of goods on his

shoulder do you mean the prisoner? - A. No, it was an officer.

Prisoner. Q. Was it an open cart, or had it a tail-board? -

A. It was open.

Q. Was there anything to prevent the truss falling out? -

A. It was impossible, because I had put it so far in the cart; I had another

large truss behind it.

JOHN FENNER sworn. - I am an officer belonging to Cheap

Ward; Alderman and I were in company together on the 3d of November, crossing,

about six o'clock in the evening, Cateaton-street, we observed a man running

with a truss on his back.

Q. Was that the prisoner? - A. Yes, and two others with

him, one of whom we knew to be a thief; we immediately pursued him to the

corner, of King's Arms-yard, Coleman-street, and there stopped him; I had never

lost sight of him; he had the goods on his shoulder when I collared him; I

asked him where he got the property, and he said a man gave him a pot of porter

to carry it for him.

(John Alderman corroborated the evidence of Fenrler).

Sutton. This is the parcel I delivered to Woodlands; here

is the bill of parcels I sent with it. -(Produces it.)

Prisoner's defence. I had been to Chater's, the

watchmaker, in Cornhill, and going down Coleman-street, I picked up this

parcel; there was another man with me, and he said, he would take it home to

his house and advertise it.

Jury. (To Fenner.) Q. Is the truss clean or dirty? -

A. Clean.

Q. What sort of night was it? - A. A very dark and dirty

night.

GUILTY , aged 25. Transported for seven years.

London Jury, before Mr. Recorder.

His trial was short and

the testimony given was scant. He was

found guilty and sentenced to 7 years transportation to the British penal

colony in Tasmania.

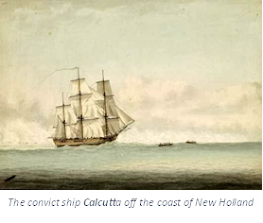

He was held in jail in

London, England until he was delivered on board the prison hulk at Portsmouth

on October 16, 1802. He was transferred

to the prison ship Calcutta and departed port on January 31, 1803

arriving in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia on October 12, 1803.

His time on the prison

ship is well-documented in the fascinating story about the prison ship Calcutta

below.

James married Johanna Clarke/Sculley/Schullah

nee Brady on November 5, 1827. Johanna,

herself a convict, had been married and widowed three times prior.

Johanna Brady first

married Owen Clarke (a convict) and had a son. Upon the death of her husband she married

James Sculley who was a free settler. She and James Sculley had a

daughter. James Sculley then died in

1818, and she then commenced a relationship with William Schullah and had 3

more children.

When Johanna married

James Dowsing, all the children took on the Dowsing surname. James Dowsing and Johanna had no children of

their own.

Sometime, after he

completed his sentence, James Dowsing was granted 50 acres next to Prince of

Wales Bay in Glenorchy. James Dowsing is

now commemorated in the naming of Dowsing Point in Hobart, near where the Bowen

Bridge joins land on the western shore of the Derwent River.

On January 12, 1839, James died at Hobard, aged 64, of 'Decay of

nature'. He was listed as a farmer. His adopted son James Dowsing, Jr. made claim

to the land granted to James Dowsing, Sr.

From the Government

Gazette, Cornwall Chronicle, 11 July 1840.

James Dowsing, Hobart, 50 acres. - (Originally James

Dowsing, senior; the applicant claims as heir-at-law — Claim dated 29th May,

1840.) Bounded on the west by 24 chains and 15 links extending southerly across

a point of land from the River Derwent along the east boundary of a location

originally made to James Miles, and thence on all the other sides by that river

to the point of commencement.

Genealogy: James Dowsing (1776-1839) was the son of William Dowsing

(1764-1844). His daughter was Mary

Dowsing (1767-1844) and her son was John S Saunders (1795-1868) and his

daughter was Mary Ann Saunders (1818-1893) and her husband was George Dalley

Burwood (1821-1845) and his father was George Salter Burwood (1789-1829) and

his father was Henry Bell Burwood (1766-1851) and his father was George Burwood

(1743-1823) and his mother was Judith Salter (1707-1773) and her mother was Judith

Farrow (1680-1718) and her mother was Anne Mewse (1654- ) and her father was Philip Mewse (1629-1673)

and his father was John Mewse (1592-1667) and his son was Simon Mewse

(1641-1719) and his son was Simon Mewse (1672-1741) and his son was Simon Mewse

(1695-1736) and his daughter was Mary Mewse (1727-1797) and her daughter was

Elizabeth Curtis (1756-1832) and her son was John Curtis Adams (1797-1873) and

his son was William Frederick Adams (1848-1907) and his son was George “Pikey”

William Welch-Adams (1867-1940).

The Voyage to Australia on

the Calcutta during 1803.

After leaving the Cape

on board HMS Calcutta Lieutenant James Hingston Tuckey wrote in his

journal about the voyage.

Lieutenant Tuckey

remarked:

In these southern seas, we were

continually surrounded by whales, and were even sometimes obliged to alter our

course to avoid striking on them.

The stormy seas which wash the

southern promontory of Africa … are despised by the British seaman, whose

vessel flies in security before the tempest, and while she rides on the billows

and defies the storm, he carelessly sings as if unconscious of the warring

elements around him.

The tedium of the

following weeks was occasionally enlivened by performances from the African

American violinist William Thomas.

To say the remainder of

the voyage was plain sailing would be to ignore the fact that it took Calcutta

until 10 October to arrive at King Island in the entrance of the Bass Straits

(she had departed Simon’s Bay on 25 August 1803). The lookouts aloft had been

anxiously scanning the horizon for land for two days before the island was

sighted and then because of an increasing breeze the ship had to stand three

miles off shore.

A ‘perfect hurricane’

commenced to blow, but had spent itself by the following morning, the day

dawning beautifully serene. It was a totally unknown coast and Calcutta

approached cautiously till the break in the land forming the entrance of Port

Phillip was observed.

A shout from the man at

the mast-head alerted all to a ship at anchor within this entrance, soon

identified as the Ocean, the companion vessel from which Calcutta had

parted at Tristan da Cunha many weeks before. This was a welcome and cheering

sight after so long at sea. Lieutenant Tuckey was unable to refrain from

another fanciful passage of prose:

... an expanse of water ... unruffled

as the bosom of unpolluted innocence, presented itself to the charmed eye,

which roamed over it in silent admiration. The nearer shores … afforded the

most exquisite scenery, and recalled the idea of ‘Nature in the world's first

spring.’ In short, every circumstance combined to impress our minds with the

highest satisfaction for our safe arrival.

After a week spent

searching for a suitable spot for the settlement, it was decided to land the

marines and convicts on the shores of a small bay eight miles from the harbour

mouth. Camp was pitched and the crews of the two ships began unloading cargo.

On the first days of our landing,

previous to the general debarkation, Capt. Woodriff, Colonel Collins and the

First Lieutenant of the Calcutta had some interviews with the natives who came

to the boats entirely unarmed, and without the smallest symptom of

apprehension.

The Convict Ship Calcutta.

HMS Calcutta was the built originally as the East

Indiaman Warley in 1788 for the East India Company but was purchased by

the Royal Navy and in 1795 she was converted to a 56-gun Royal Navy ship. This

ship of the line served for a time as an armed transport.

Between May 1802 and January

1803, the Navy had Calcutta fitted out as a transport for convicts being

sent to Britain's penal colonies in Australia. She received new armament in the

form of sixteen 24-pounder carronades (a type of cannon) on her upper

deck and two six-pounder guns on the forecastle. Captain Daniel Woodriff

recommissioned her in November 1802 and sailed her from Spithead, England on 28

April 1803, accompanied by Ocean, to establish a settlement at Port

Phillip. Calcutta carried a crew of 150 and 307 male convicts, along

with civil officers, marines, free settlers and some 30 wives and children of

the convicts. The Reverend Robert Knopwood kept a journal on the voyage.

Calcutta arrived at Teneriffe on 13 May; five

convicts had died on that leg, suggesting that many had probably been embarked

already in bad health. She reached Rio de Janeiro on 19 July, and the Dutch

colony at the Cape of Good Hope on 16 August 1803.

While Calcutta

was at the Cape, a vessel arrived with news that Britain was now at war with

the Batavian Republic. The colony's Dutch commodore sent a representative

aboard Calcutta to demand her surrender and that of her contents. While

the representative waited, Woodriff spent two hours preparing her for battle.

He then showed the representative her sailors and marines at their guns, and

told the Dutchman to inform the commodore that "if he wants this ship he

must come and take her if he can". To speed up the preparations, William

Gammon, the master's mate, had asked the convicts if any would volunteer to

fight and work the ship. All volunteered. The commodore gave Woodriff 24 hours

to leave, saying that he "did not wish to capture such a large number of

thieves".

On 12 October 1803, she

reached her destination; by this time another three convicts had died. Of the

eight convicts that died, one had drowned in an escape attempt at the Cape and

one was shot on attempting to escape.

At Port Phillip, David

Collins, the commander of the expedition, found that the poor soil and shortage

of fresh water made the area unsuitable for a colony. Collins wanted to move

the colony to the Derwent River on the south coast of Tasmania (then Van

Diemens Land) to the site of current-day Hobart. At least 13 convicts were

transferred on to Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania), Australia. Woodriff refused the

use of Calcutta, arguing that Ocean was large enough to transport

the colony, and that he was under orders to pick up naval supplies for

transport to England.

In December 1803, Woodriff

sailed to Sydney where he took on a cargo of lumber. At midnight, on 4 March

1804, Woodriff landed 150 of his crew and marines to assist the New South Wales

Corps and the Loyal Association, a local militia, in suppressing a convict

uprising in support of the Castle Hill convict rebellion, a revolt by some 260

Irish convicts against Governor King. Afterward, the commander of the marine

detachment on Calcutta, Charles Menzies, offered his services to the

governor as superintendent of a new settlement at Coal Harbour, an offer

Governor King accepted. Another Calcutta officer, Lieut. John Houston, accepted

an appointment as acting Lieutenant Governor of Norfolk Island while Major

Joseph Foveaux was on leave.

Calcutta left on 17 March 1804, doubled Cape

Horn and reached Rio on 22 May. In reaching Rio, she had thus circumnavigated

the world in ten months and three days.

She arrived at Spithead on 23 July 1804.

_______________________________________________

Australian Joint Copying

Project. Microfilm Roll 87, Class and Piece Number HO11/1, Page Number 338

Source Description

This record is one of

the entries in the British convict transportation registers 1787-1867 database

compiled by State Library of Queensland from British Home Office (HO) records

which are available on microfilm as part of the Australian Joint Copying Project.

Comments

Post a Comment